Some questions about Shakuhachi in Ukiyo-e

Some questions about Shakuhachi in Ukiyo-e

In the Japanese prints, known as Ukiyo-e, or images of the floating world, the objects are depicted with high precision, including the most delicate details.

So, we can see musical instruments drawn with accuracy, and when details are showed, they look realistic. Shamisen are pictured with stings, pegs, bridge, even the knot used to tie up the strings to the body is correct. When they appear being played, the hands and fingers positions, the way the plectrum (bachi) is hold, everything is about right.

It happens the same with other instruments, like koto, hand drum (tsuzumi), shinobue, etc.

But shakuhachi representations are usually partial, showing only part of the instrument, normally the root end. When shakuhachi are depicted complete, usually they show no utaguchi, the holes positions are wrong; even they appear with more than five holes.

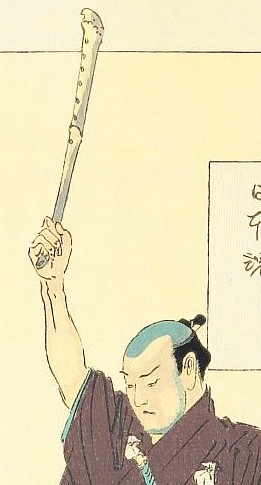

The engravings showing people playing the instrument are scarce, more often they appear hanging on the back of the characters, or inside the bag, or being used as a weapon. And when they are showed being played, the positions of hands and fingers are not right

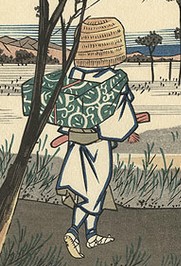

There are many examples. Komuso monks are painted sometimes with the tengai, or basket shaped hat, and all the accessories, but the shakuhachi are usually inside the bag.

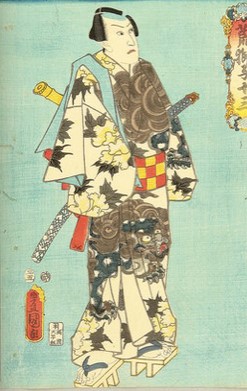

More often, shakuhachi appear in the prints depicting kabuki theatre plays, specially in the hands of the otokodate characters, legendary knights who protected villagers. The third more frequent group of prints showing shakuhachi describe the story of prince Genji, a novel written in the beginning of XIth C.

I looks like the painted shakuhachi are not real flutes, but “atrezzo” instruments, used in the kabuki plays, where shakuhachi appear frequently, but it is never played, it is just part of the character’s costume.

It seems outstanding that I could find only a few examples of detailed shakuhachi rightly pictured, after watching more than one hundred prints.

In XIX C.,there are several engravings made by Kiyonaga, where the shakuhachi are shown played by komuso. Though it is not possible watching the utaguchi, the instruments look realistic, also the positions of hands and fingers.

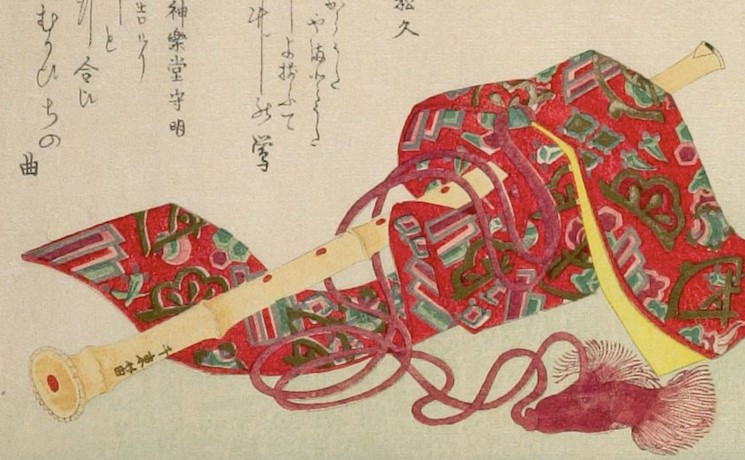

There are also two prints by Utamaro, where the shakuhachi, though partially depicted, include an utaguchi. The one in the included picture has an utaguchi inlay, and the holes look correct. In the other example, there is an utaguchi with no inlay. Only the upper part is drawn, so we cannot see the holes of the flute.

The last examples are the only ones I could find of shakuhachi possibly copied from real models, the first is by Toyokuni I (XIX C.) but it is a five nodes bamboo.

The other image was made by Gosei, a Hokusai disciple.

Shakuhachi was not a popular instrument in Japan. Everybody heard about it, and the word is known (though often with a very different meaning), but I met many people from Japan who never actually saw or listened to a real instrument.

It might be the case of another disappearing tradition, like it is happening all over the world. But a closed watching to the old images suggests that also in the XVIII and XIX C., shakuhachi was scarce to the point of having nearly no faithful representation, but some exceptions. And I wonder why, nearly none of so many artists, along more than two hundred years, had a real model to copy.

Perhaps, the legendary origins of shakuhachi in Komuso monks monasteries, and the influence of Bushido, the samurai code, could give some meaning to the facts. Maybe shakuhachi was not an instrument to play in public, out of the meditation, cult, and ceremony purposes. The traditional repertoire, Koten Kyoku suggests individual, inward interpretation, and it looks like that music was made to be played, more than listened to, just like Western plainchant.

This article is an excerpt of a longer more detailed one that I will publish in my web page, and it wants to be a call of attention on a fact that looks strange to me. Maybe somebody more expert than me could add information and help to clarify the subject.

Jose Seizan Vargas (Tokio – Madrid, Spring 2015)